Over the past week or so there’s been some scuttlebutt here or there about “the state of” the competitive Mortal Kombat, or Netherrealm Studios, sub-communities. A few people had their opinions, some of them thought-provoking, some not, but everyone seemed to arrive at a shared feeling of something amiss. Most of it is directly focused on the latest release, Mortal Kombat 1, which has had some technical hiccups that are well worth critique, but I think the problem far supersedes any one title, or even a particular game community. It is one that has been a long time coming, that was sort of test-ran in the NRS communities before it began to infect other fighting game communities.

I’ll probably end up repeating it a dozen times after, but there is a certain type of cretin who will read this and think they finally found the boogeyman to demonize. They’ve had this feeling of disconnect, and I’m Fred Jones taking the mask off of Old Man Jenkins saying “here’s who to hate.” If you think this way, kindly remove your head from your ass and see the bigger picture here. This is nobody’s “fault,” it is a natural occurrence that came about due to many different factors in a large and complicated world. Do I think certain actors benefit more from this kind of occurrence and thus have more reason to preserve it? Of course; survival is built into our DNA. But if you want to even start to change people’s thinking, it’s probably best to set the table and establish that there’s even a tangible “thing” to focus on.

So I’ll write about the “thing”; in honor of Mortal Kombat, I’ve called it The Great Konsumer Shift.

When Mortal Kombat X came out in 2015, it came pre-packaged with the ESL MKX Pro League. ESL, even then, was probably the biggest esports production company there was, and it brought a level of production, professionalism, and, most importantly, money to a still-burgeoning sub-community. I’ve often joked that NRS communities has a quite polarizing population split of literal children and forty-year old lifer schizos; that’s a little hyperbolic, but it does tend to skew quite young. And for a lot of those young people, they were introduced to these communities with the idea that there was decent money to be made playing. You ever wonder how SonicFox became the number 1 earner in fighting game esports with a bullet? MKX ESL was the start of that.

Better yet, this was all done from the convenience of your home, as everything except the finals and mid-season events were done online. Sure, MKX had the same crappy delay-based online structure as its predecessors, but if you could make $2-300 from a Sunday competition, what was the downside? Not only did these ESL qualifier cups open MKX up to competitors in Europe and the CIS and (eventually) Latin America, but they were not region-restricted inside of those areas. A highlight of any big typical fighting game major was that a lot of individual regions would finally meet up and test their heavyweights against the other’s. With the ESL Pro League, that was no longer the case. Instead of having to settle for the weekly Florida or NYC stream, you could watch the best in all of North America fight it out in these online tournaments for 8 weeks straight. Because you qualified based on points, attendance and consistency were imperative, which means that you would regularly see the same players week after week as they struggled to stay afloat.

As I mentioned, NRS sub-communities are full of people who are young, young enough to not have an attachment to our hoary institutions or the sense of communal prestige (not money) that was earned with wins at those tournaments. The biggest tournaments would still get pot bonuses from WB and you could make decent money there, but nothing paid out quite like ESL, and nothing with as much convenience. You could save up for a flight, a hotel, price of entry and food for the weekend, or you could play at home and earn more money than you would have made placing even 2nd at something like NEC or SCR. There was never really a choice, unless you had a real dedication to wanting to go and play offline specifically.

If all that wasn’t enough, MKX eventually became MKXL, and it came with a major upgrade: rollback netcode. MKX went from having a substandard online experience to probably the top of the genre almost overnight. Even the best netcode is not going to perfectly model the offline head-to-head feel, but dammit if it isn’t close enough! Not only that, MKXL had a $500,000 spread across both the Pro League circuit and its amateur-focused Challenger Cup. First prize at the finals was far less than the Capcom Cup of that year, but the spread was more generous to those who didn’t get first, and it only took 8 weeks instead of the entire year.

Lastly, it’s worth noting that despite having an international tournament series that mostly took place online, the format was relatively simple to follow. ESL hosted everything, the schedule was consistent, and the points spread was standard across all tournaments. If you won, you got points, and the players with the highest points at the end of the season qualified for the finals. This also only happened over a period of roughly 3 months, so it was only tied to offline events if they happened in that window, and even then rarely so. The lack of interregional splitting also made it so there wasn’t a bunch of different events to tune into, and the very large tournament sizes were handled by ESL’s skilled organizers and professional website. Even a casual fan could understand the stakes, the players, and the progression of the brackets.

This was a time of great growth for the NRS communities, and while I didn’t much care for the game, I can admit that MKXL and the ESL MKX Pro League were incredibly successful at bringing in new people. But with that influx of players came what I would consider the two major expectations that became the cornerstone of the Great Konsumer Shift:

- There needed to be a tournament circuit and/or invitational that rewarded tens, if not hundreds of thousands of dollars every year, to both pros and amateurs alike

- Free-to-enter online tournaments needed to be maintained in addition to the offline circuit that already existed, preferably ones that come with a substantial reward for the time invested

If those two preconditions weren’t both met, or perhaps half-assed, then the health of the communities would be seen as dire. It might sound strange that a game in which you could earn up to potentially $100,000 for winning could be “dying,” but I’m not really here to make a value judgment, just calling it as I see it.

With those two conditions came predictable consequences. One was that in order to maintain this consumer expectation of big money competitive circuits, some deals with the devil were going to be made. In the case of the NRS circuits, that came in the form of a break with ESL as their sole partner in these endeavors. With Injustice 2, Warner Brothers partnered with marketing company Intersport, who roped in many other international marketing firms and sponsors to help construct the Injustice 2 Pro League. The amount of cooks in the kitchen was glaringly obvious in the final product, which was an intensely convoluted 7-month long process that still paid out huge in the end. This set the standard going forward – a marketing firm would handle the production of the finals while the legwork of running the tournaments would be slobbed out to whomever was able to handle it. The traditional offline majors were involved now, but the online tournaments were not only now spread out throughout the year, but region-locked in the various continents as well. In other words, it became more like its direct competitor, the Capcom Cup of Street Fighter IV-VI but with one big change – there was still big money for the finals at the end of the year, but the dizzying heights of getting a $500k investment, a chunk of which went to online tournaments? Those days were gone.

With a void now for weekly, un-region-locked online tournaments, it was up to the community members to do something on their own. And luckily some did – tournament series that were clearly trying to replicate that old ESL feel sprung up, like the War of the Gods series for Injustice 2. Tournament series of this ilk have continued even up through the current games, and the effort is truly impressive. The caveat, of course, is that impressive though they might be, these are ultimately independently driven affairs which couldn’t possibly hope to match the kind of money and professionalism that ESL was offering. Nevertheless, they were and are important community hubs that run way underfunded and for free, as is the expectation.

You also may have noticed that with community-led efforts at tournament series, official tournament series, and major tournaments that exist outside of both of those, it may seem like a lot to keep with. Add in the convoluted point structures for the main tournament that take place across many different regions, and once-simple and easy to follow storylines suddenly become a bit muddled. Like any sport, a big part of engagement with people who aren’t at the higher levels is both from local participation and following the ups and downs of a season. But even some pretty hardcore sports fans don’t pay attention to literally every single game, even those with shorter schedules like American football. At best, they will follow their local team, or only really start tuning in later in the season when the postseason, the most exciting time with the most stakes and clear, season-long storylines, begins to take shape.

To compare those to what’s going on in the NRS communities, with various online series happening at the same time as a major circuit, it can feel like you’re having to follow the NFL, the USFL, and the XFL all at the same time. One is obviously head and shoulders above the others, but imagine that NFL pros also played in the other two leagues at the same time and we had to judge their skill according to that logic as well. If you win a USFL game that happened with NFL talent in it, does that make you better than the NFL players? Difficult to say.

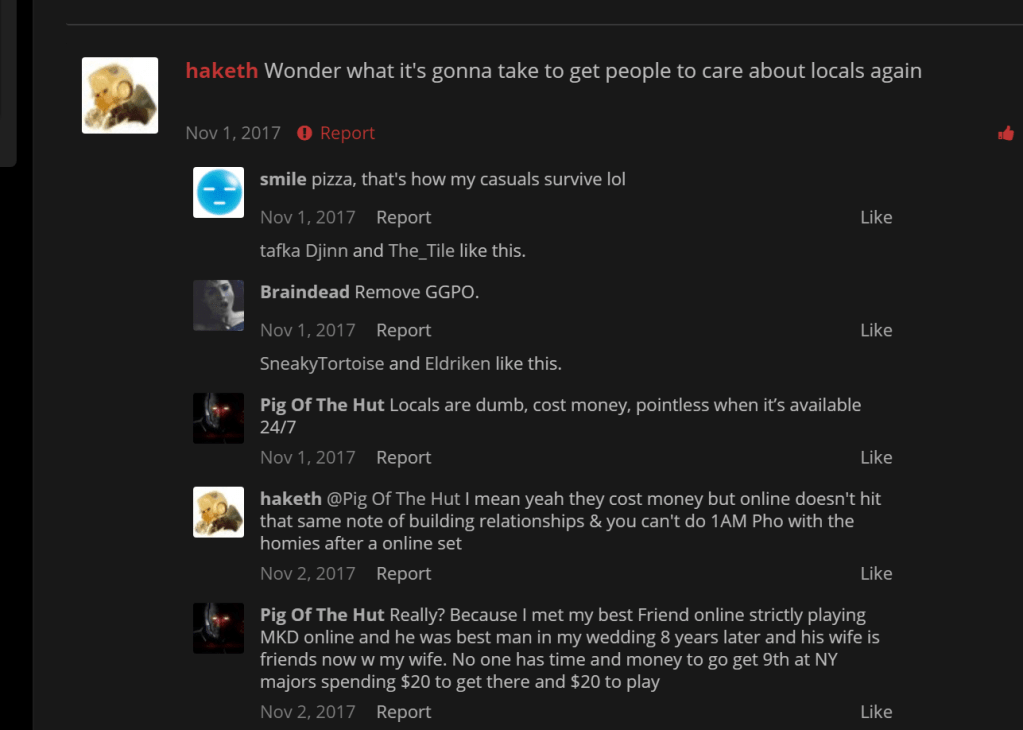

But what of the idea of following local heroes? At one time, we might have used offline majors to decide which regional talent was truly knowledgeable at the game, with stories naturally forming based off the backs of those results. Internationally that may still be the case – both the EU and certain parts of the CIS and Latin America have proven to be incredibly capable – but at least in the US? Regional battles have all but ceased. With how prevalent online events became after rollback became the standard, with the best of the best a mere DM away, there was often an incentive to not go out and play locally. Why waste the money?

That’s not to say that there are no locals, that would be an absurd generalization. Even in MK11, there was an incredible Florida v. Texas money match team battle that honestly stole the show. But this was organized on its own, didn’t have a return match, and was mostly just a fun one-off. It wasn’t like the winner was considered the most dominant region – that time has just moved on, especially when international competition got more normalized. Without that sense of regional pride, finding a local, let alone starting one, was even less appealing.

So you’ve got big money that kind of swallows up attention from most things, also competing with the more grassroots online stuff that was kind of left on the vine after MKXL, and through all of this most people don’t represent regions, and the same pros from the big money play in every online tournament. It is a lot to follow even as a fan, and even more confusing sometimes as a player to know where to invest your time. Offline majors, with their legacy and usually higher prize pool, are enticing, but they are also, in 2024, a major expense, more akin to a yearly vacation than something you could go to twice in the year. In that instance, I think a lot of the NRS communities are more than willing to just follow individual players or streaming teams, whether that be SonicFox or Rewind or TNS or The Kollosseum, and that becomes their way of participating. Much easier to get a sense of what’s going on that way, because if you try to follow everything, it can be hard for anything to feel important other than what’s paying out the big bucks.

On paper that makes sense, but since there’s not really an inherent gatekeeping or skill level keeping pros from being pros in these fighting game communities, we are left to decipher something from the huge mass of content that exists out there now. When you can only realistically follow certain people, those people’s opinions naturally become your gauge on how the community is doing. Sadly, once the expectation of the consumer becomes the somewhat contradictory ideas that playing for big money at big tournaments is the most important thing but there must also be a good sample size of online tournaments that also pay out, and the same people tend to dominate both, one kind of opinion tends to suck up all the oxygen: that of the people trying to (or have a delusional believe they can) make a living off this stuff.

And it will never be good enough!

It all traces back to those two expectations. The MK1 Pro Kompetition, sad to say, isn’t great – it’s of the same mold as the previous marketing firm-led endeavors have been, which is subpar. Especially in lieu of SF6’s astronomical Capcom Cup grand prize of $1 million, there’s a real sense of dissatisfaction with the $100,000 offered up by the Pro Kompetition. Online tournament series have been active and happening for a while, but again, the thing about the Great Konsumer Shift is if the big money isn’t there, then no amount of online tournaments could fill that void, and the base feels entirely slighted. Add to that the very real online desyncing issues currently plaguing MK1, and you get people starting to believe everything is dead on arrival, even if hundreds of thousands are online playing the game every day.

Again, I’m not offering up that any of this is fair or unfair, or there is any one individual or entity within the communities that made it this way. It just simply is. I can only write down what I observe and follow the predictable consequences that arrive from that reality. Some may think that those expectations rely entirely too much on free labor from a community not flush with cash, as well as put too much power and attention on the rights holders and developers, who don’t have any real obligation to put on these circuits, especially as esports continues to underperform as a broadcast sport. Fair to think, and real conversations about how to saddle those two extremes could exist, but as I said at the beginning, you have to diagnose an issue before you can start treating it.

What’s interesting to me as well, especially after COVID and the natural refocus to online tournaments as a way of keeping the spirit alive, is that I believe this Great Konsumer Shift has been happening subtly everywhere.

The NRS communities were ripe for this kind of thing because their competitive bedrock was only solidified very recently, in the last ten years or so, and the playerbase skews very young. Games like Street Fighter and Guilty Gear and Tekken have far more history with FGC institutions, much bigger international competition, and a stronger presence in having a local infrastructure across these countries. This kind of shift was never going to happen as quickly as it did in the NRS communities, but I think we’re beginning to ascend to that point.

I look at the 2023-24 Capcom Cup, which has more money than has ever been at stake: a cool $1 million. It is also vastly more difficult to follow, with tons of online events that matter quite a bit snuck in between majors, qualification requirements so convoluted that even people who travel and place high at major offline events constantly still haven’t qualified, and all the other hallmarks of a largely marketing-first approach to these circuits. Also like with the NRS communities, Capcom Cup stands out because of the money, but there’s all sorts of other events, some with big-ish money prizes and some not, that exist online. You’ve got the ICFC, the TNS weekly tournaments, the Can Opener series, Red Bull will pull some kind of invitational tournament every now and again, and so on and so forth. Eventually we’ll get the KFC Honey Gold Mt. Dew Sweet Lightning Kumite and we will like it!

The only way to make heads or tails of it if you’re not in the thick of it yourself is to follow a player or creator that aggregates the results and can make it entertaining enough to be worth a follow. Being a “casual” fan of this stuff doesn’t exist anymore, you’re almost forced to be a follower and watch hours of content to understand it. And because of that (necessary!) gravity that those players and creators take up, their particular, not-always-aligning-with-reality discontent in a system that mostly benefits them becomes a de facto critique of the communities themselves. Sound familiar?

The perception of the communal vitality of games now rests in the clumsy, quick-to-tweet fingers of a privileged few, and it’s not because anyone made it that way or even wants it that way. But these spaces have spent many years under the thumb of what we now know to have been an exceptionally wrongheaded belief that we were the future. And certainly, winning a million dollars for a tournament sounds like that future is here. But, like with the NRS communities, I can’t help but wonder if that future instead is one where the anxiety of an extremely particular group defines the culture more than the games and tournaments themselves. Will people continue to invest a lot of time following communities where its tastemakers appear increasingly removed from the masses and their fanbases make participation kind of exhausting?

I’ll reiterate for a final time that I’m not saying that there are only cons to all this. I can certainly see the upsides, as none of these things are bad in a vaccum. I also know the reality that the market has, for better or worse, rejected esports, particularly fighting game esports, as something with mass appeal in the US and elsewhere. In light of that, this Great Konsumer Shift seems to come with a pretty obvious downside that will naturally slide rhetoric toward the apocalyptic, particularly with those who stand to gain the most from that shift. It’s hardly a conspiracy, and if broken down logically, any one could see that these are natural responses to events that happened, something a little more tangible than “vibes”. But it can be hard to notice from the inside looking out, so I hope that what I’ve put down here can speak to some of you out there. Until next time.

Leave a comment